Looking ahead, at the next few months (or years), what do you hope for?

If I asked what would you wish for, would your answer change at all?

Although we often use the words hope and wish interchangeably, there’s a huge difference. Both are future oriented—for things we want to happen.

When we wish for something we want to happen, we do so in a passive way: wanting something to happen to us without any effort on our part.

I wish we would win the lottery.

When we hope for something we want to happen, we actively participate in bringing it about.

I hope my children grow up to be good, generous, loving people.

So then, when we consider that hope is a theological virtue, what we’re saying is that we are actively participating with God.

The theological virtue of hope can be defined as trusting in the promises for the Kingdom of God and cooperating with God’s grace to make the future happen.

Participating with God involves

trust.

- I trust that I am doing my best, taking personal, proactive responsibility.

- I trust God to do the rest.

Balancing the two – personal responsibility and trust in God – is a challenge. Most of us struggle with one of the two extremes:

Too Much God, Not Enough Me

–OR–

Too Much Me, Not Enough God

Too Much God, Not Enough Me

You know the story of the man and the flood?

A man who lived by the river heard a radio report predicting severe flooding. Heavy rains were going to cause the river to rush up and flood the town, so all the residents were told to evacuate their homes. But the man said, “I’m religious. I pray. God loves me. God will save me.” The waters rose up. A guy in a rowboat came along and he shouted, “Hey, you in there. The town is flooding. Let me take you to safety.” But the man shouted back, “I’m religious. I pray. God loves me. God will save me.” A helicopter was hovering overhead and a guy with a megaphone shouted, “Hey you, you down there. The town is flooding. Let me drop this ladder and I’ll take you to safety.” But the man shouted back that he was religious, that he prayed, that God loved him and that God will take him to safety. Well… the man drowned. And standing at the gates of St. Peter he demanded an audience with God. “Lord,” he said, “I’m a religious man, I pray, I thought you loved me. Why did this happen?” God said, “I sent you a radio report, a helicopter and a guy in a rowboat. What are you doing here?”

When our reliance on God comes at the neglect of human action, we are not practicing the

virtue of hope. Instead, we practice some wish-based “Cheap-Hope” where

God will provide becomes equivalent to saying

God will do it all for me.

Jesus invites us to participate in bringing about the Kingdom of God. (Read more about participation in my post about The Good Shepherd and Sacraments.)

Sometimes, all we can do to help a situation is pray. And we should always pray. But when we can do something more–and it falls within our realm of responsibility–we should do so.

God created us in his image and likeness (Genesis 1:26-27), and bestowed upon us gifts and talents that he expects us to use (recall the Parable of the Talents, Matthew 25:14-30). We need to take these seriously as we practice the virtue of hope.

Too Much Me, Not Enough God

Then, there are those of us who take it to the other extreme: relying on human action alone and excluding God.

We recognize that the person in despair lacks hope. But too often this isn’t an inability to practice the virtue of hope. Rather, despair–hopelessness–is a sign of a serious depression. Help is available for those who need it.

Who struggles with the practicing the virtue of hope?

- The Type-A who obsesses about every little detail

- The Control Freak who cannot let go

- The Worrier who is filled with anxiety

- The Complainer who loses perspective

When we think that everything is up to us, we are not practicing the virtue of hope. Here, the lack of hope involves the failure to trust God.

When Maureen was asked to be the Spiritual Director for the next Christ Renews His Parish (CRHP) retreat, she was overwhelmed. “I can’t do this; I’m not qualified.” The Continuation Committee recognized her gifts and talents, but Maureen was filled with anxiety. “This is an enormous responsibility. I cannot possibly lead and guide these women on their journey.” In prayer and conversation with her loved ones, Maureen came to see that she was assuming that she alone was responsible for the direction of the retreat. Rather than envision her leadership as participating with God, she feared it was all up to her. Once she grounded herself in the virtue of hope, she was able to accept. Throughout the process of formation, Maureen had to constantly remind herself that she was not in this alone. Rather, she was working with God: doing her best and trusting God to work in, with, and through her.

Whether it’s our parenting, our professional career, or our relationships, practicing the virtue of hope means that we are participating with God. Moreover, we are inviting God to participate with us in every nook and cranny of our lives.

Practicing the virtue of hope also means participating with others. We need to allow and encourage others to participate to the best of their abilities. That means putting down our “If you want it done right you have to do it yourself” banners. The social justice principle of subsidiarity means that we let each person do for themselves what they can. There is goodness in that. It’s how Jesus did things, too.

Like any virtue, practicing hope is something that we can get better at doing. As a teen, I often prayed the Serenity Prayer.

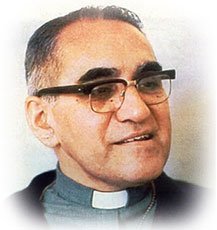

As an adult, I find that the Prayer of Oscar Romero speaks to the depths of my heart as I struggle to become better at practicing the virtue of hope.

It helps, now and then, to step back and take a long view.

The kingdom is not only beyond our efforts, it is even beyond our vision.

We accomplish in our lifetime only a tiny fraction of the magnificent enterprise that is God’s work. Nothing we do is complete, which is a way of saying that the Kingdom always lies beyond us.

No statement says all that could be said.

No prayer fully expresses our faith.

No confession brings perfection.

No pastoral visit brings wholeness.

No program accomplishes the Church’s mission.

No set of goals and objectives includes everything.

This is what we are about.

We plant the seeds that one day will grow.

We water seeds already planted, knowing that they hold future promise.

We lay foundations that will need further development.

We provide yeast that produces far beyond our capabilities.

We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that.

This enables us to do something, and to do it very well.

It may be incomplete, but it is a beginning, a step along the way, an opportunity for the Lord’s grace to enter and do the rest.

We may never see the end results, but that is the difference between the master builder and the worker.

We are workers, not master builders; ministers, not messiahs.

We are prophets of a future not our own.

“Hope, Colorful words hang on rope” © Depositphotos.com/Ansonde

If you enjoyed this post, Please Share