The Truth About Love

Have you ever had one of those random moments in life—personal or professional—when someone asks you something, and when you open your mouth to respond, you’re amazed by the profound insight that comes out? You know you said it, but the wisdom had to have come from God?

Well, years ago, while teaching in Austin, I took a group of students to work at an orphanage in Mexico. In addition to showering the children with attention and affection, we did a bunch of home-improvement style projects – from cleaning to painting to repairs. The poverty was staggering. While we helped both physically and financially, it was abundantly clear that our charity was not going to bring about a real and lasting change.

That evening, we did the Mission-Trip-Circle-Up conversation to discuss and process our day. One student, Travis, was extremely conflicted: “I feel really good about myself, but I feel guilty for feeling that way. We have so much, and they have so little. It just doesn’t make any sense; I don’t like the fact that I feel so good about myself.”

I suggested to Travis that “feeling good” was not reflecting some kind of “superiority,” but rather he felt good because he was participating in true agapic love. In the Gospel of John, Jesus called us to love one another as he loved us; to participate in agape. This was not a “to-do-list” task, but an invitation. The act of selfless giving in service (and in love) feels great because in it, we experience the divine.

And it doesn’t matter which kind of love we’re talking about: philia (friendship love), eros (passionate love), storge (family affection), or agape (unconditional giving of oneself for the good of another).

What a profound “God-is-love” truth.

The act of selfless giving in love feels great because in it,

we experience the divine.

For some reason, when talking about love, it’s a lot easier to get our heads around what love means when we take romance out of the equation. But this same dynamic of selfless-giving-feeling-great applies to all four loves.

Allow me to explain:

Remember Erich Fromm’s definition of love (from Art of Loving 19)? I concluded my post on dependency (I Need You to Need Me), with this:

Mature Love “is union under the condition of preserving one’s integrity” or individuality.

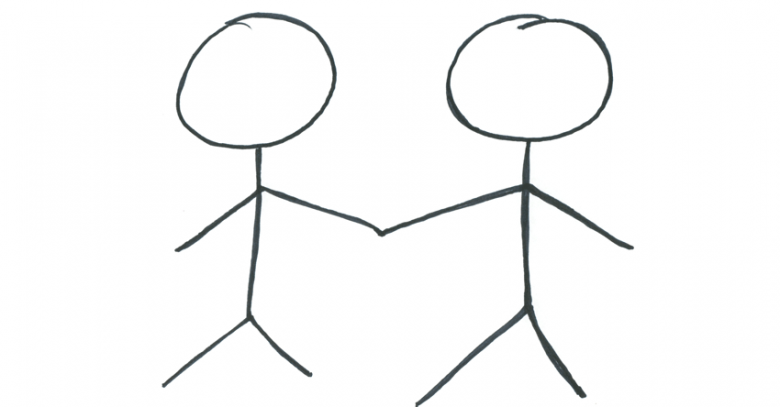

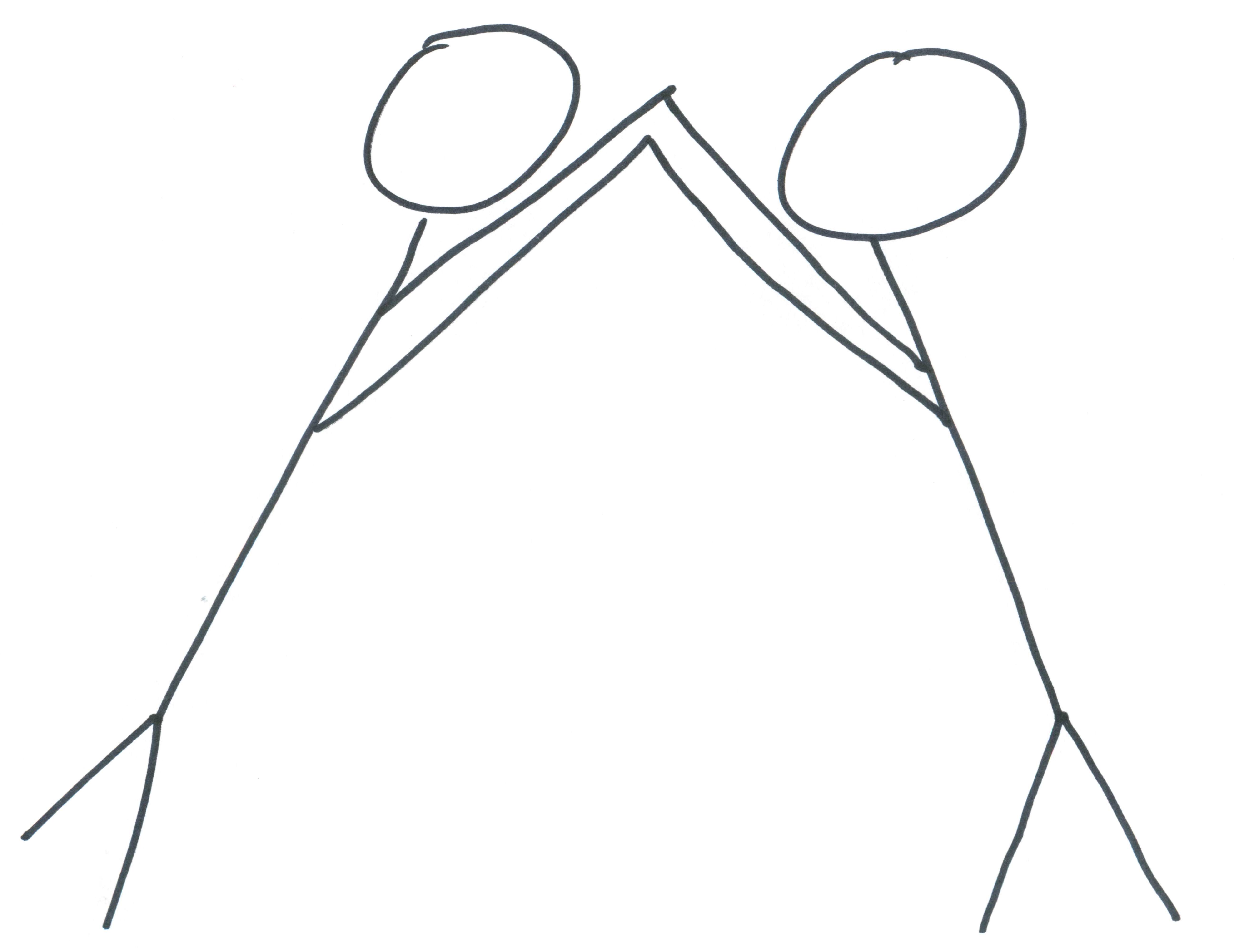

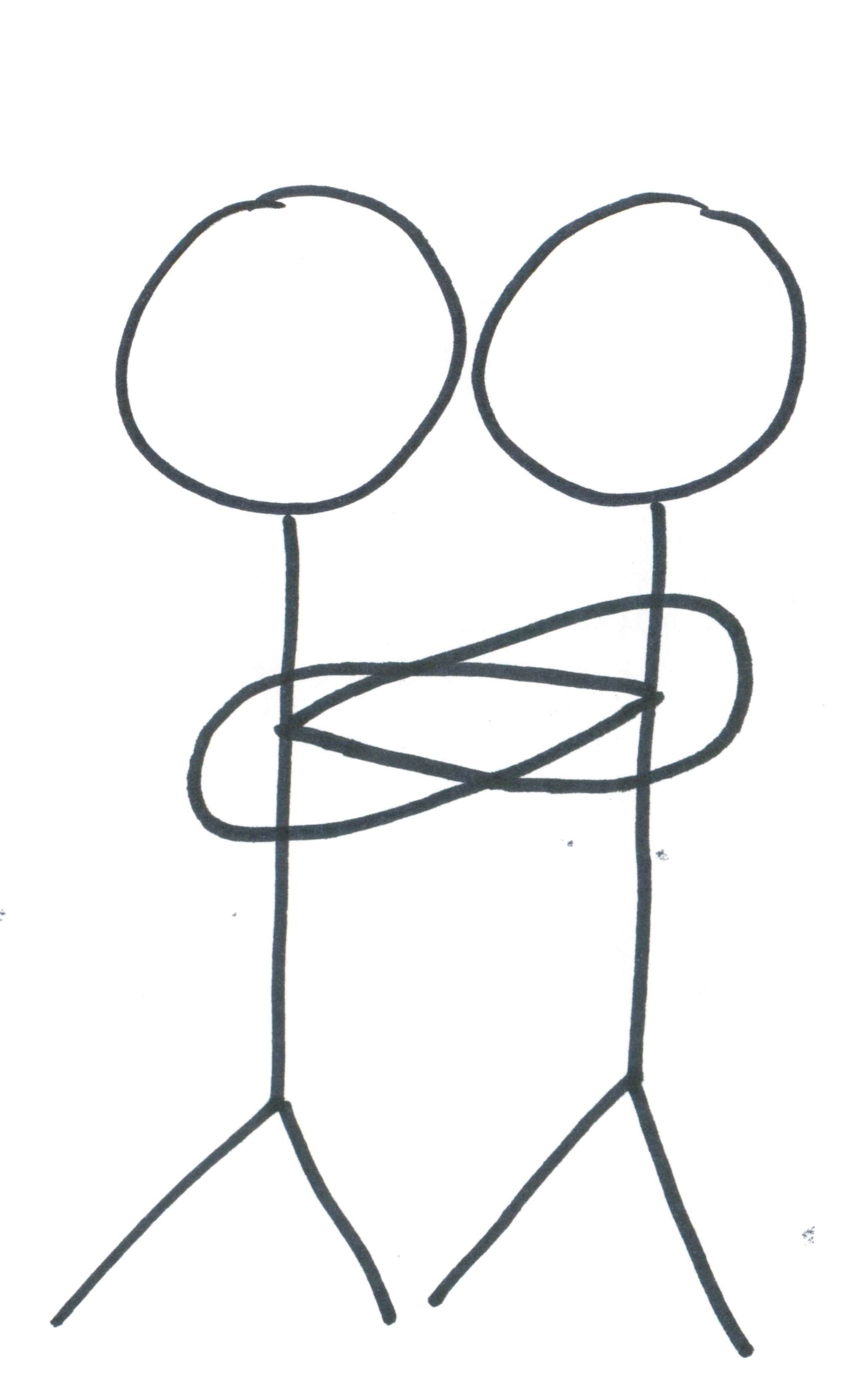

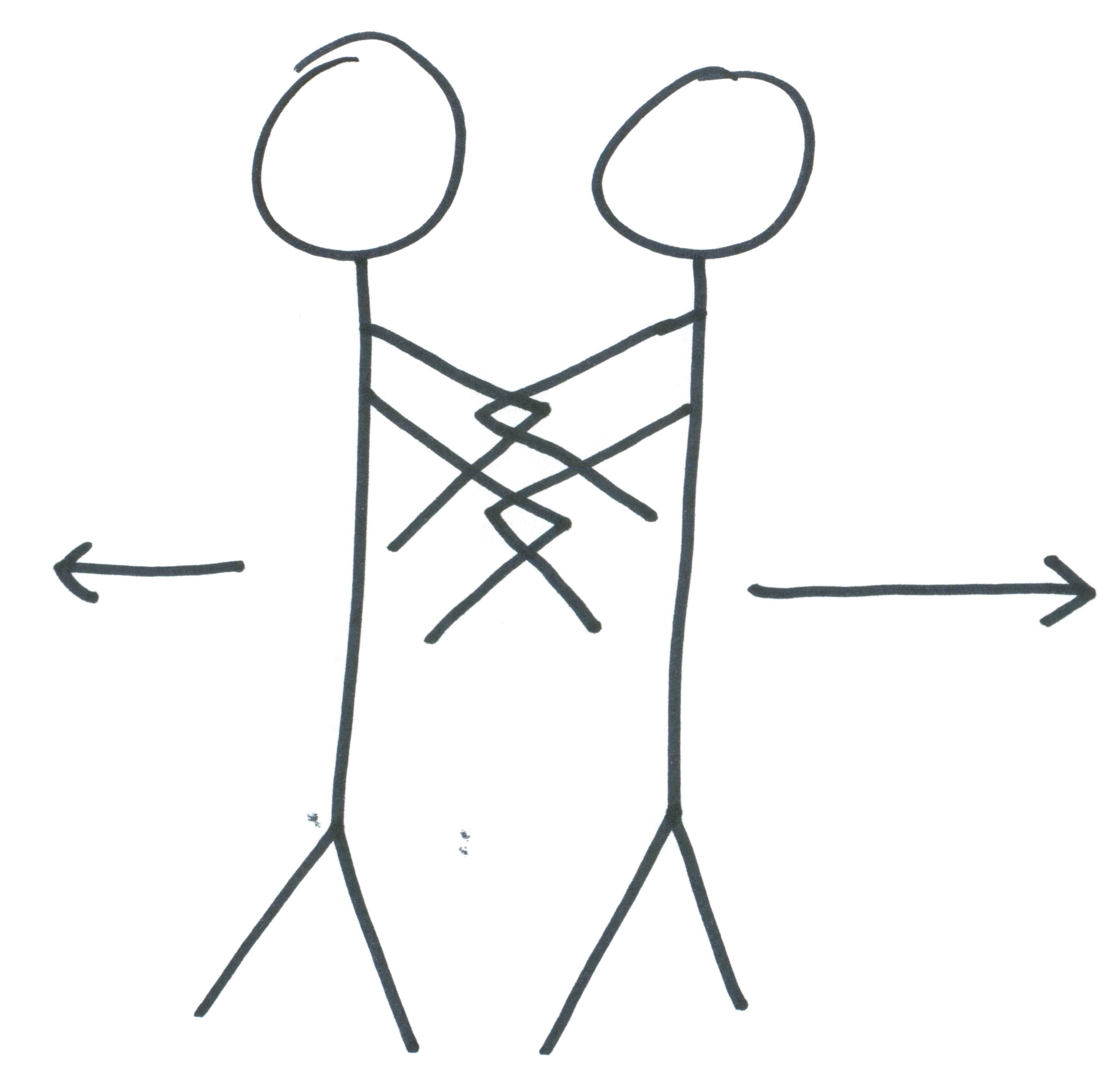

If we were to diagram that one, it would be two stick figures choosing to come together to hold hands, maintaining their integrity, freely capable of individuality. This “pattern” can and should apply to all four kinds of love.

In all four types of love, one can and should be able to give of oneself without giving up one’s identity.

Going on, Fromm names four basic elements that are common to all types of love: Care, Responsibility, Respect, and Knowledge.

- Care – When we care about someone or something, we are concerned for their well-being. When we don’t care, we don’t love.

- Responsibility – Instead of limiting our understanding to some assigned “duty,” Fromm goes to the root of the word:

- Respect – Without the element of respect, the element of responsibility “could easily deteriorate into domination and possessiveness” (26).

It’s about respecting the person’s human dignity – in God’s image (not your image). This means allowing the other person to grow and unfold as they are (not as you would have them become…even if you have the best of intentions).

Love means letting people be free to be who they are, right now.

- Knowledge – As we seek to become closer with people—friends and family as well as our beloved—we come to see how many layers there are to truly knowing someone. Knowledge of a person is key to real, mature love.

Fromm points out that “Care, responsibility, respect and knowledge are mutually interdependent.” They are all attitudes found in love, and they are each needed to balance one another.

So then love is all these things:

- Agape, Eros, Storge, Philia

- The will to extend one’s self for the purpose of nurturing one’s own or another’s spiritual growth – M. Scott Peck

- Union under the condition of preserving one’s integrity and individuality, practiced with care, responsibility, respect, and knowledge – Erich Fromm

Love is all of this and more.

Painters by Bart Everson licensed under CC BY 2.0