Within a week of starting college I met a guy and completely fell in love.

It was not only a textbook example of the what-not-to-do insights offered in You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling, but it would serve as my introduction to the dynamic of dependency.

When I excitedly told my favorite high school teacher about my new-found sweetheart, I thought his response was rather odd: “Ah, you’ve found yourself a symbiotic partner.” The boyfriend, a biology major, thought for a moment and explained, “Well, symbiosis is a mutually beneficial relationship between a parasite and a host… which is an unusual way of describing our relationship, but they need each other… and so do we.” And I’m pretty sure we felt affirmed by that description of our relationship.

Retelling this story, I feel a little like an audience member in a horror flick, wanting to scream: “RUN!”

I need you. I cannot be happy without you.

When M. Scott Peck discusses the misconception that dependency is love, he describes it as parasitic, and focuses on the lack of freedom.

“It is a matter of necessity rather than love. Love is the free exercise of choice. Two people love each other only when they are quite capable of living without each other but choose to live with each other.” (The Road Less Traveled, 98)

When talking about dependency, my favorite author to reference is

Erich Fromm (d. 1980). Fromm was a German social psychologist and philosopher who wrote the international bestseller

The Art of Loving in 1956. Like Peck, Fromm never actually uses the Greek term, but definitely talks about “Mature Love” in the

agapic sense, as a skill that can be taught and developed.

What I really appreciate about Fromm’s work is the detail with which he describes the dynamic of dependency, or Symbiotic Union. There is a passive form of symbiotic union (the submissive, dependent person) and an active form (the dominant, co-dependent person).

The passive, submissive, dependent person escapes from the unbearable feeling of isolation and loneliness by symbiotically becoming part and parcel of another person who directs, guides, and protects them (The Art of Loving, 18).

I am nothing without you; I feel special because you care so much about me.

The active, dominant, co-dependent person escapes from the isolation and loneliness by symbiotically making another person part and parcel of himself (or herself, as it were). The ego is enhanced, especially since the passive person worships their symbiotic partner (Ibid).

I need you to need me; it makes me feel special to be so needed.

The thing to remember here is that both the active person and the passive person are dependent on each other. They both need each other. No one is being forced into submissive roles here, and this mutually beneficial arrangement—where everyone’s needs are being met—is a large part of that initial attraction.

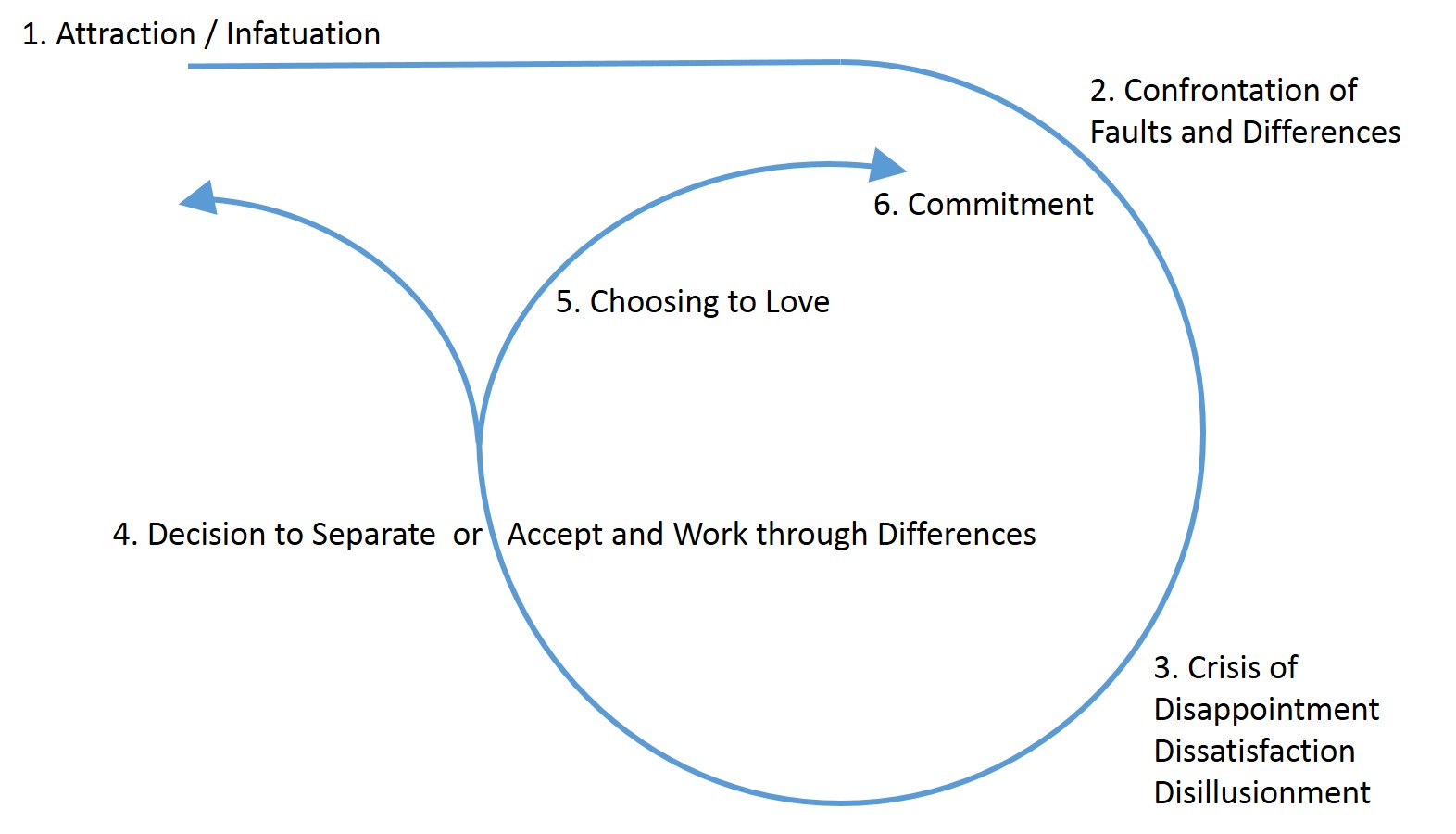

Post-college, I attended an adult-enrichment workshop in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia in which the speaker described six different patterns of unhealthy relationships. Asking for two volunteers, she had the “couple” kinesthetically demonstrate the different patterns she described. I found the activity to be profoundly enlightening and came to use it in my classroom with teenagers. It fleshes out Fromm’s explanation of the symbiotic union with relatable examples.

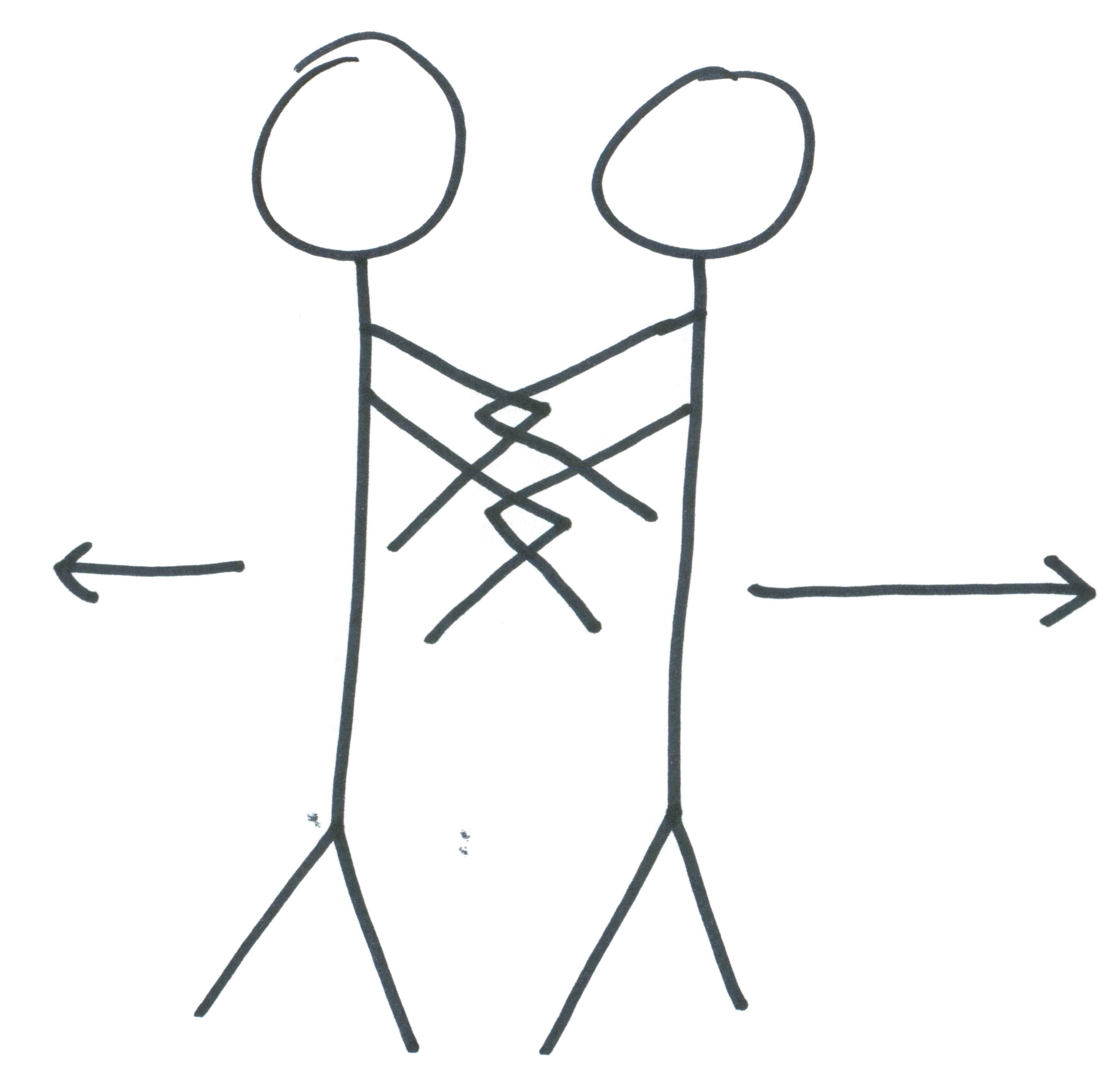

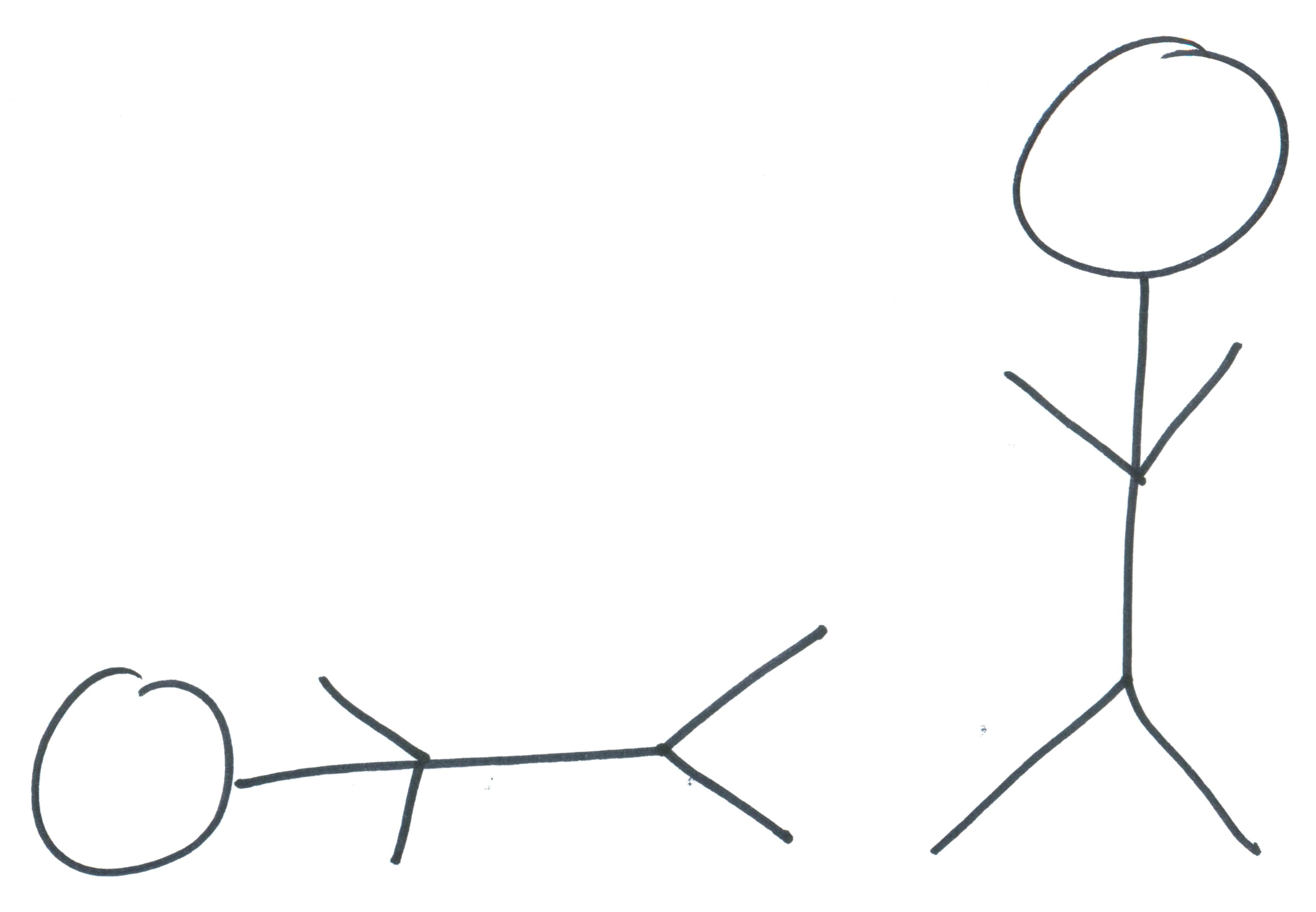

What follows is my uber-sophisticated stick figure representation of the bodily positions and corresponding description.

Patterns of Dependency in Unhealthy Relationships

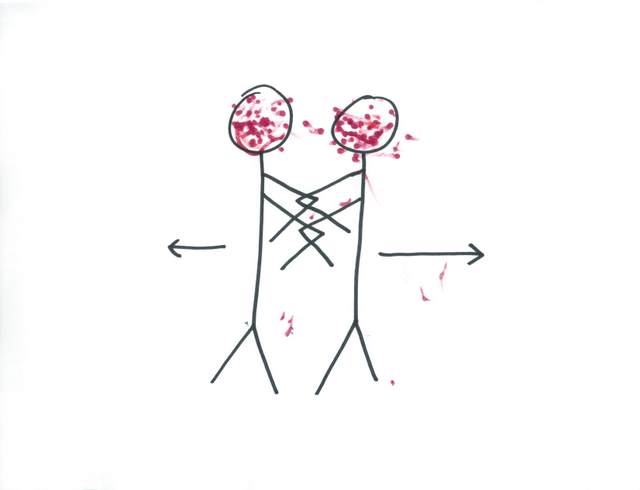

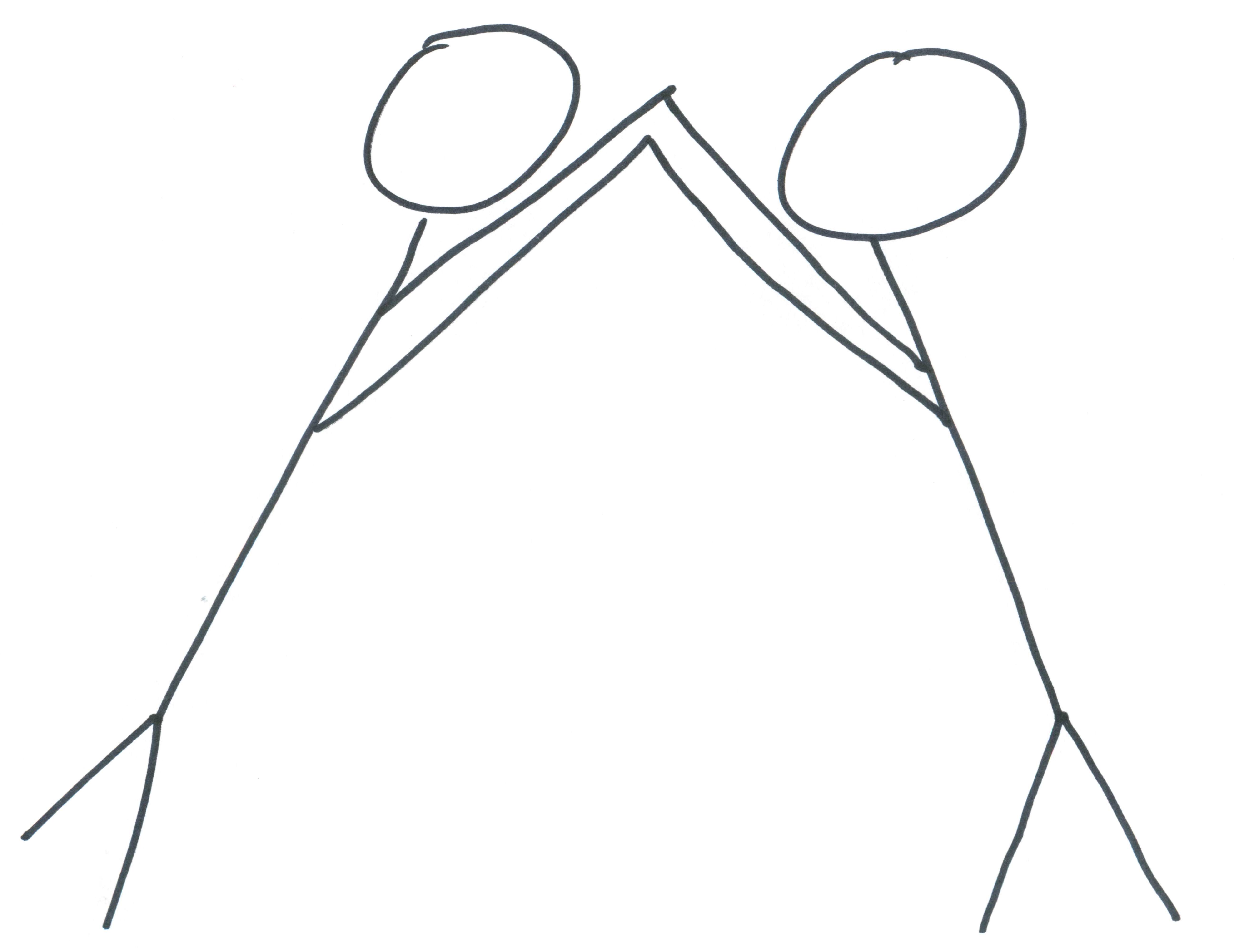

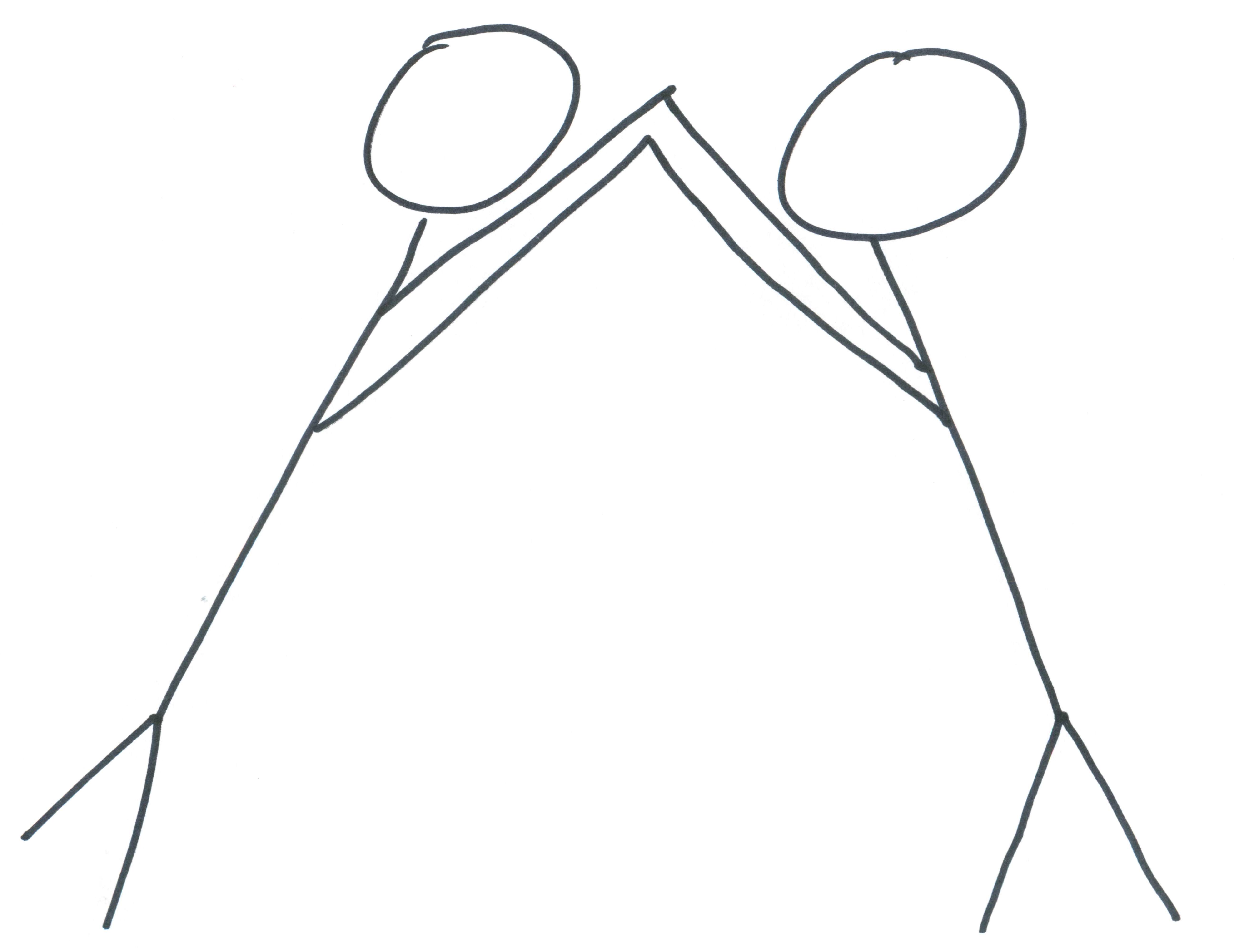

1. A-Frame – The kinesthetic set-up here may be difficult to see in the form of a stick-figure drawing: both people are leaning on/into each other, each putting their full body weight upon the other. Their bodies are slanted towards each other like the sides of the letter “A.”

The people in this relationship are incapable of functioning independently; even if one attempts to do so, the other will literally fall without their partner’s support.

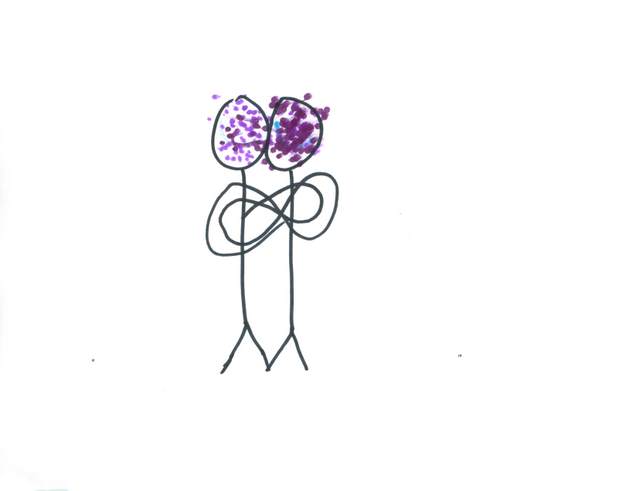

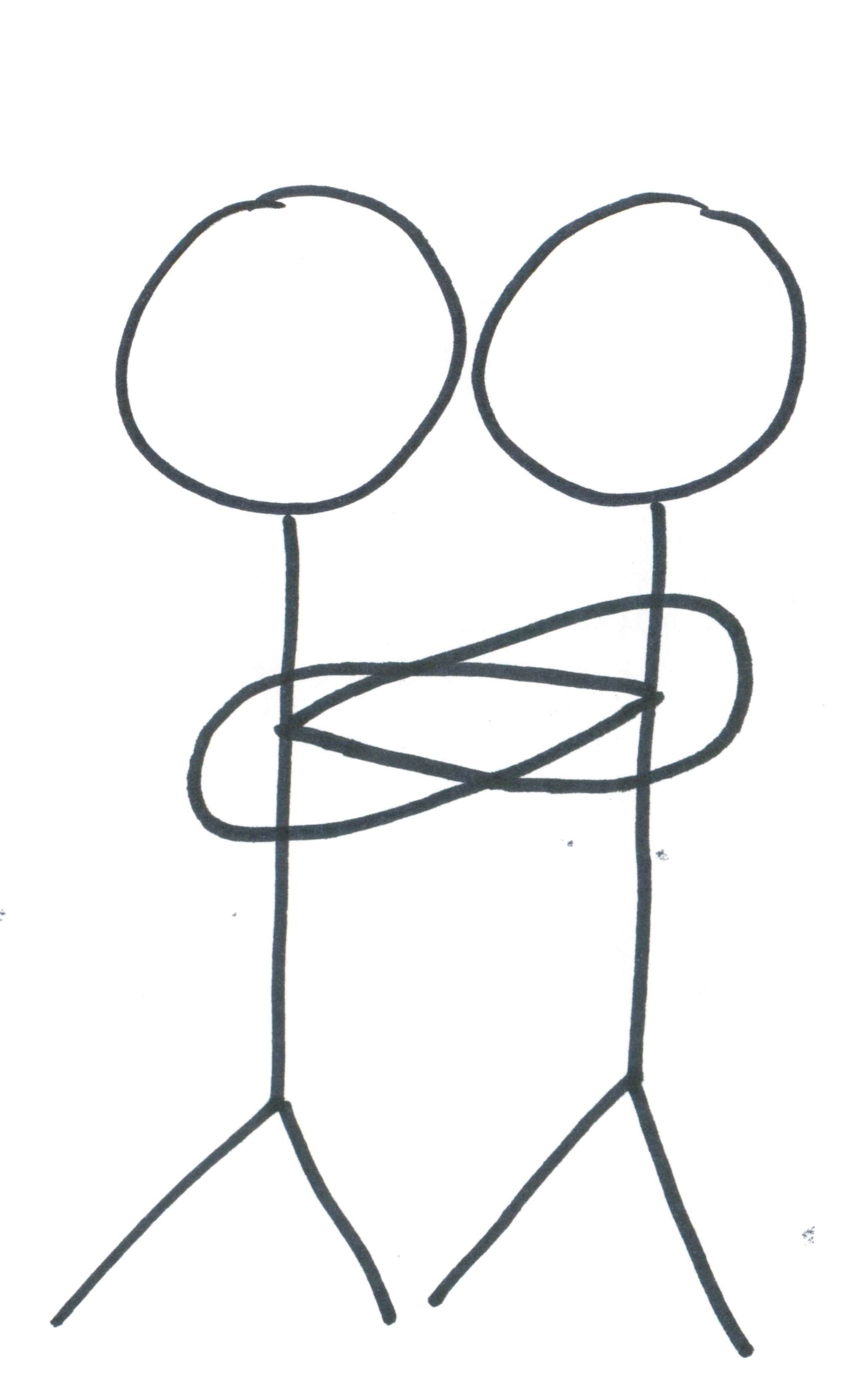

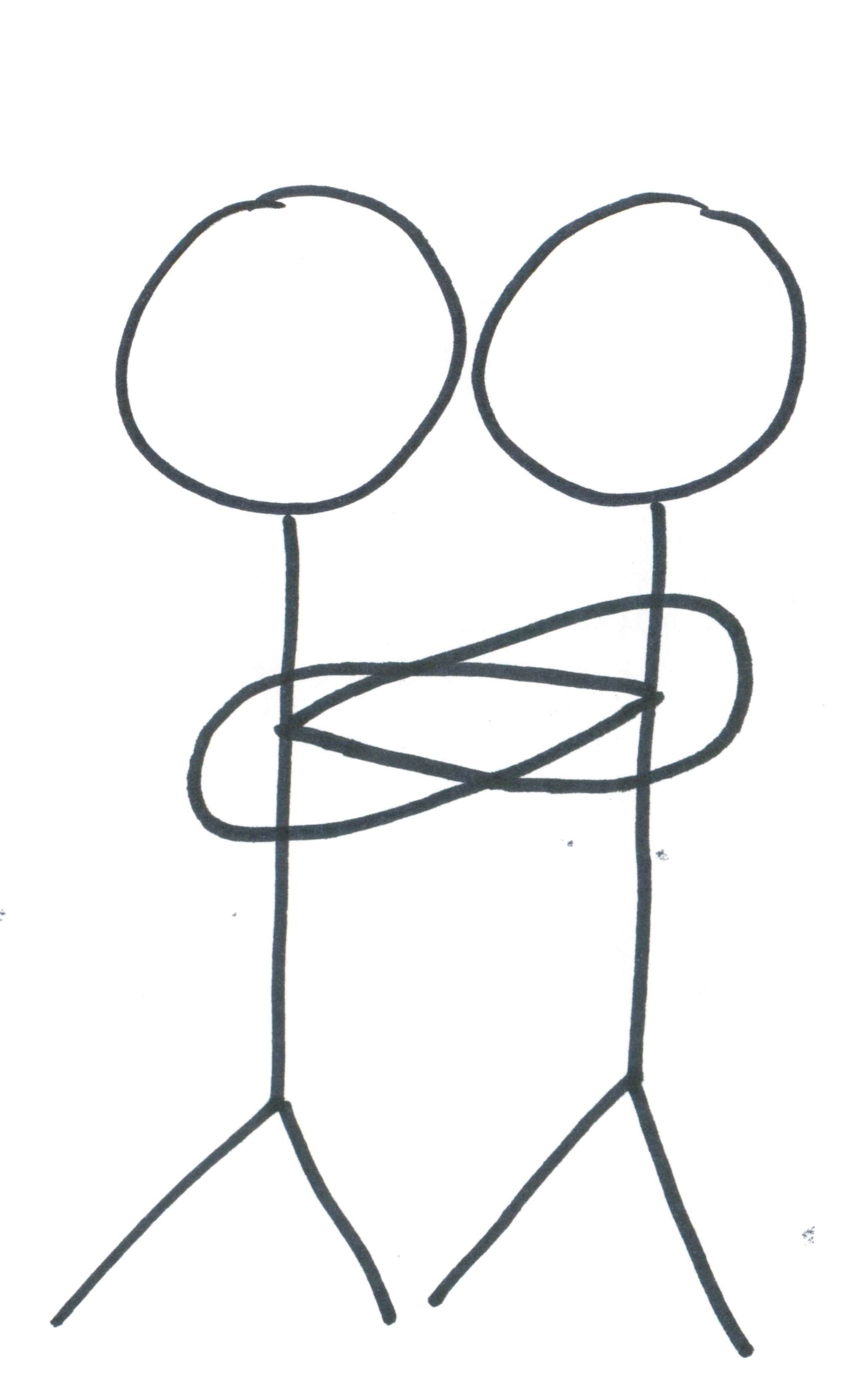

2. Smothering – The kinesthetic set-up has the two hugging closely…and never letting go.

The people in this relationship may be physically (overly affectionate) or emotionally smothering. These are the couples whose identities have become so merged that those around them refer to them as a unit (recall “Bennifer” or the teen couple from the Zits comic strip known as “Rickandamy”).

3. Master-Slave – Kinesthetically, one stands firmly while the other is on hands-and-knees.

There are clear active (dominant) and passive (submissive) roles in this relationship. One is the “boss” while the other willingly follows orders. Remember no one forces their partner into a role; the “slave” needs the guidance of the “master” as much as the “master” needs the “slave.”

You don’t know her like I do.

He cares so much about me, it makes me feel so special.

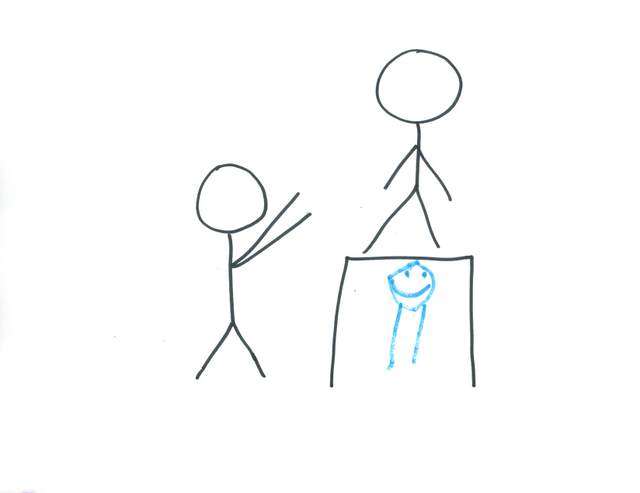

4. Pedestal – The kinesthetic set-up here has one standing atop a chair or desk while the other stands on the floor, looking up to their elevated partner.

In this relationship, the (elevated) “hero” helps the (lowly) “troubled” person, which often involves saving “troubled” from some sort of crisis. Initially, “hero” feels great with all the self-satisfaction involved in helping someone, and “troubled” feels incredibly cared for.

I love who you are becoming.

This dynamic becomes problematic if one of the two attempts to break out of their prescribed unequal roles. While “troubled” may certainly worship “hero,” it is important to note that “hero” may not necessarily desire these unequal roles in the relationship. It’s not just up to “hero” to step down; “troubled” also needs to stop putting “hero” up on the pedestal. Ironically, resentment over the unequal roles in this relationship is usually the reason for its demise.

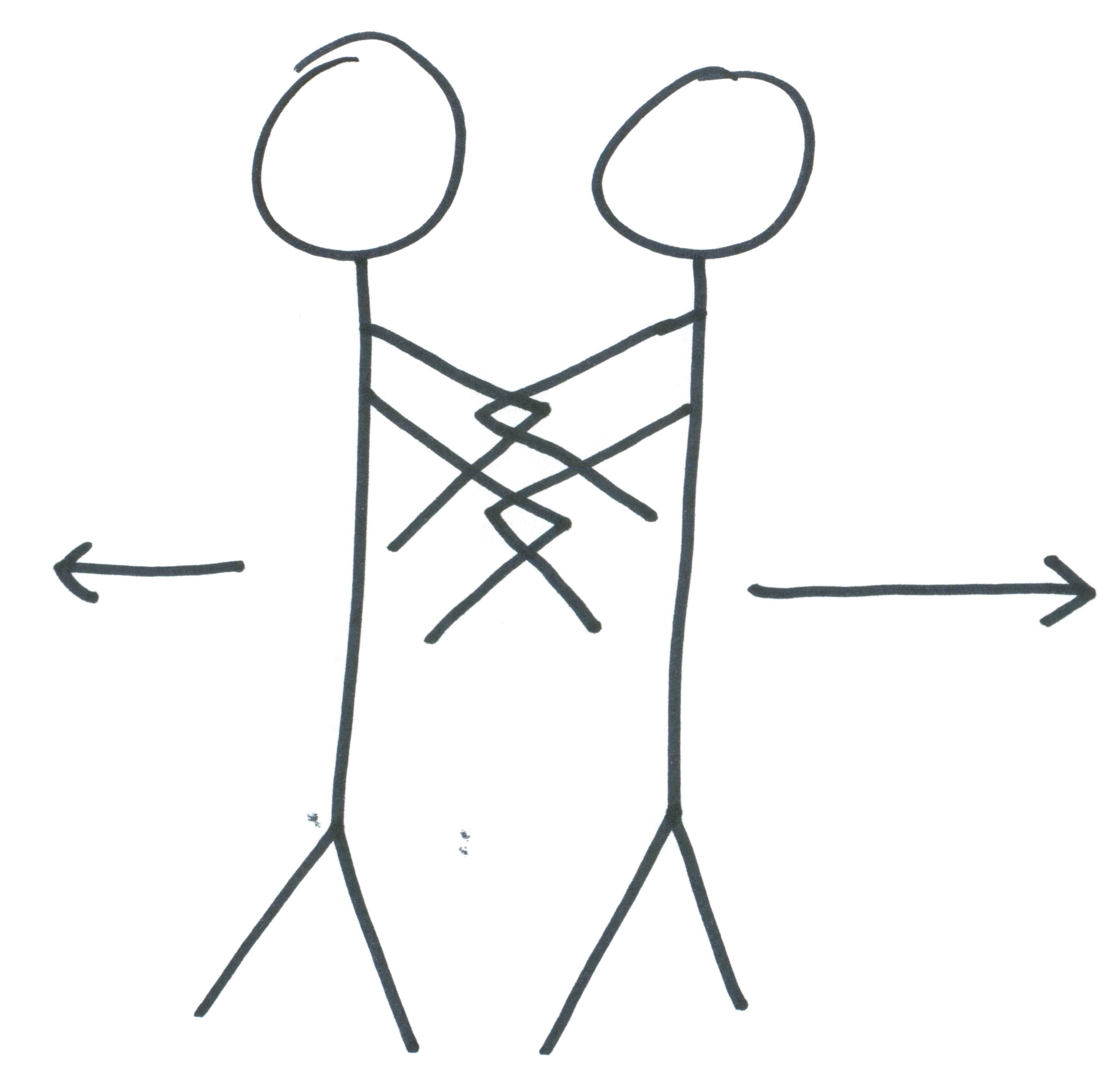

5. Contract – Kinesthetically, the two are back-to-back and interlock elbows. Then, they each attempt to walk in the direction they are facing… constant conflict ensues.

The parties in this relationship have long since lost that lovin’ feeling, and have somehow managed to come to an (often unspoken) agreement to just stay together. This couple is constantly fighting or bickering, but never actually works on any of their problems. They prefer being unhappily together to being alone. Stuck in the comfortable rut of their relationship, they need each other so that they’re not alone.

I used to think that this pattern applied mostly to older, married couples (staying together “for the kids”). However, the teens I taught quickly pointed out that many of their peers were in these relationships. A fear of loneliness can prompt a person to do ridiculous things.

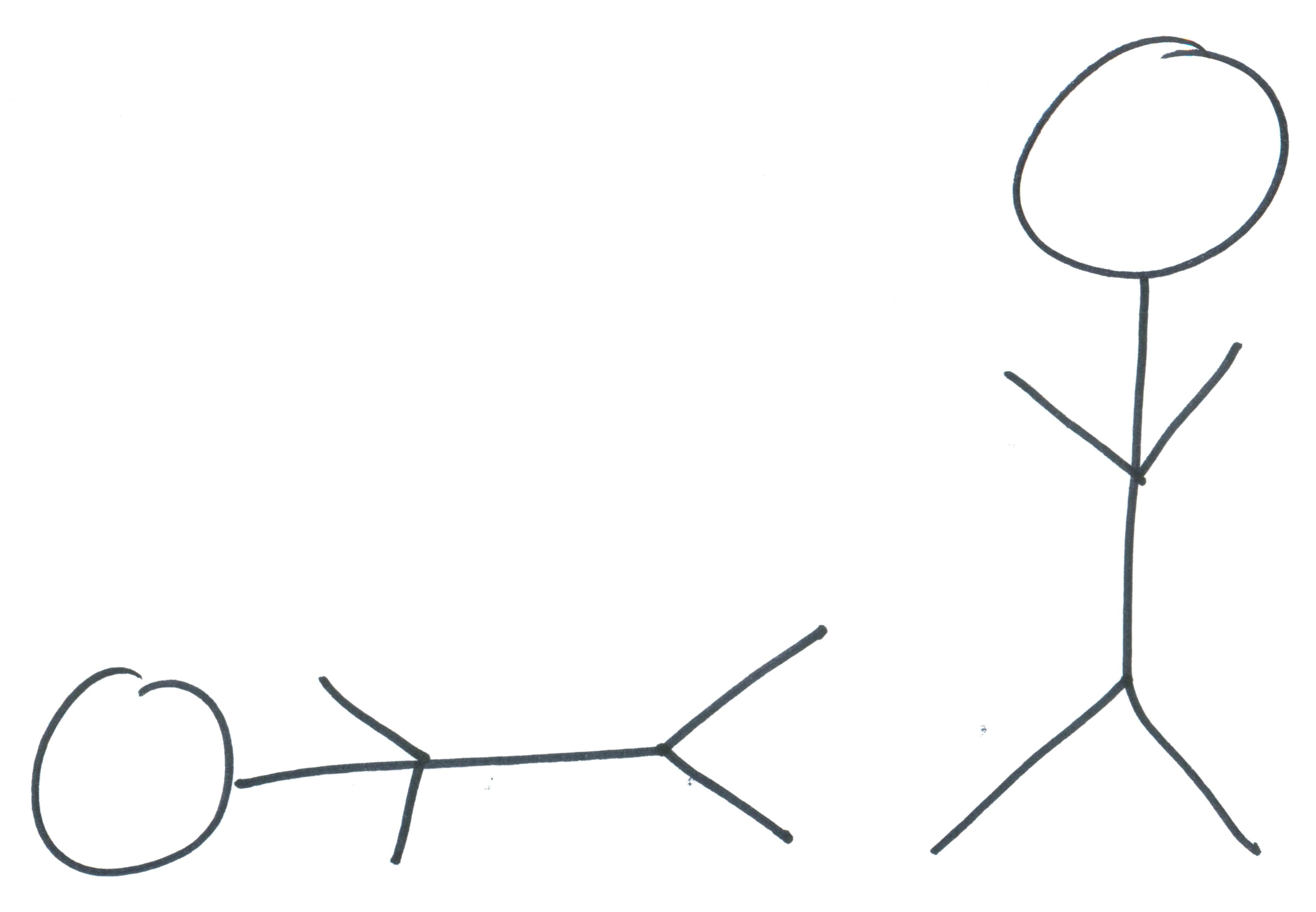

6. Martyr – The kinesthetic set-up has one lying on the floor while the other stands nearby.

The martyr willingly sacrifices their own needs and desires for the sake of the “standing partner,” often enabling the “standing partner’s” own unhealthy behavior. The martyr’s actions appear incredibly generous, and the “standing partner” benefits from all the attention.

I do so much for you!

At first glance, the “standing partner” looks to be in charge, but the martyr controls this relationship. How? Perhaps by manipulating through passive-aggressive guilt, by quietly punishing the other by chronically being late or forgetting things, sulking when things don’t go their way, blaming others for their failures, playing mind games, and so on.

When I discussed Peck’s definition of love (in What Do You Mean?), I made a comment that it’s often difficult to understand why self-love is so important without discussing dependency. Well, here we are: A person who does not have self-love is like half a person who is looking for another half a person to fill the void within and make them whole. (Side note: THIS is what is SO WRONG with that oft quoted line from the movie Jerry Maguire, “You complete me.” But I digress.)That’s not a “gift of one’s self.” That’s dependency, not love.

You were created in the image and likeness of God. You have human dignity. Love extends from this gift of wholeness and dignity.

Erich Fromm incorporates self-love into his definition (emphasis in the original, Art of Loving 19):

Mature Love “is union under the condition of preserving one’s integrity” or individuality.

Giving of yourself does not mean giving up your identity.

Know yourself, be yourself, love yourself, and share that amazing self with another person.

THAT is love.