I have my Grandmom’s chin. So does my mother, my aunts and uncles, most of my cousins, and my younger son. When I was a teen, I noticed that Grandmom’s sister, Aunt Helen has this same chin, and when she agrees with you on something, she sticks out that pointy chin, presses her lips together, and v-e-r-y slowly nods her head three or four times. Then I noticed that Grandmom often does the same thing. And so does my Mom. And now I even do it.

There are things we pick up from our family of origin whether we like it or not. Some of them are innocuous and make us smile. Other times, it’s a bad habit–or worse an immoral behavior.

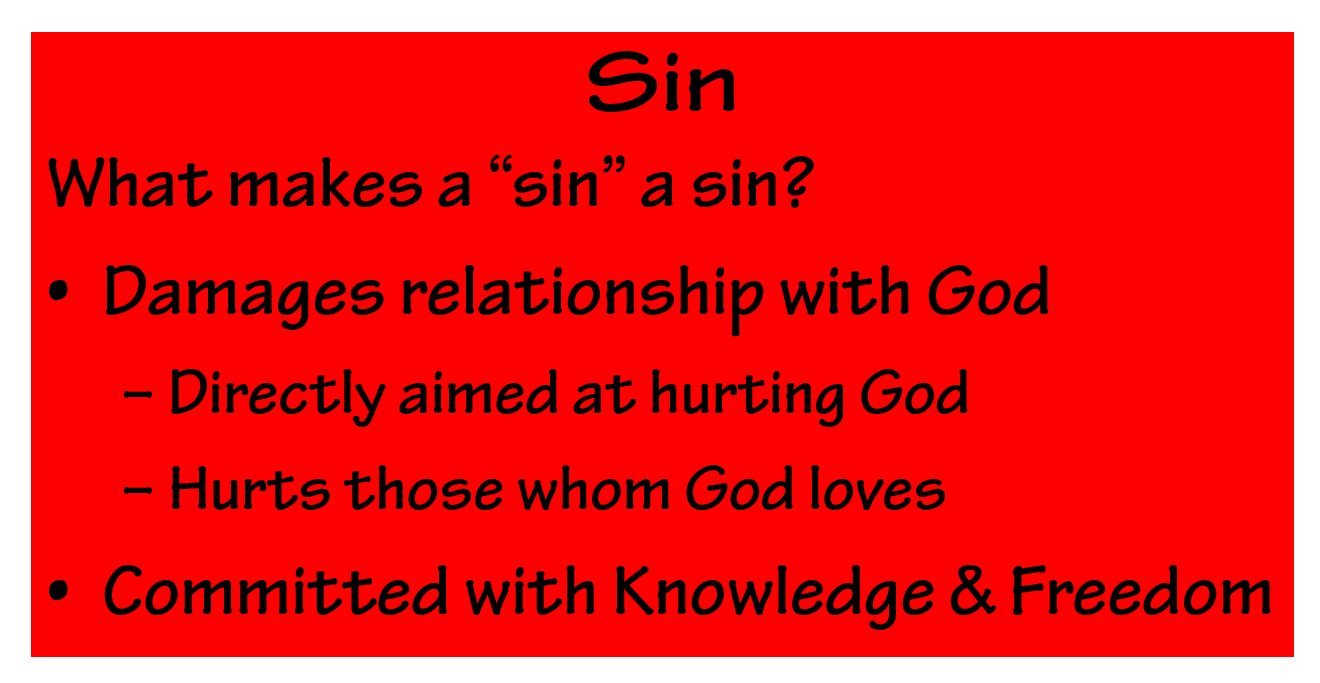

What if a person was raised in a racist home? How can we say that’s wrong if that’s what they were taught?

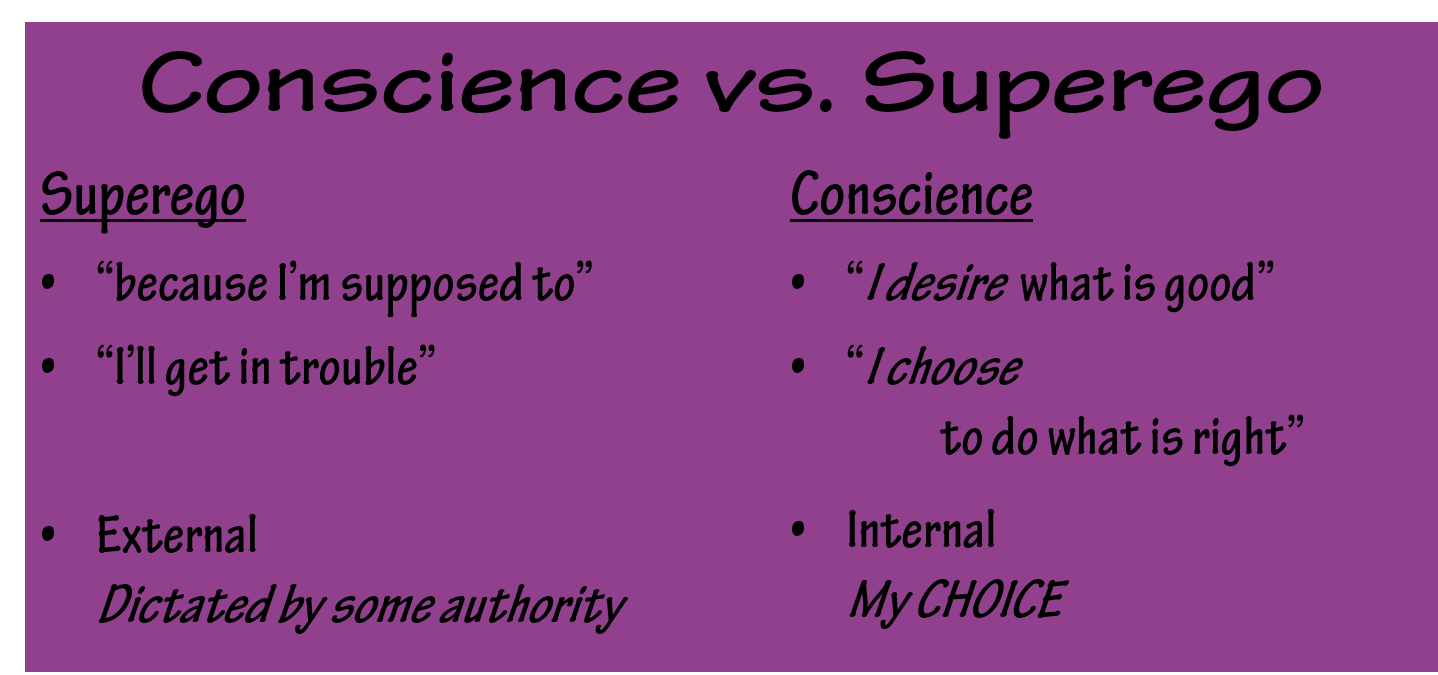

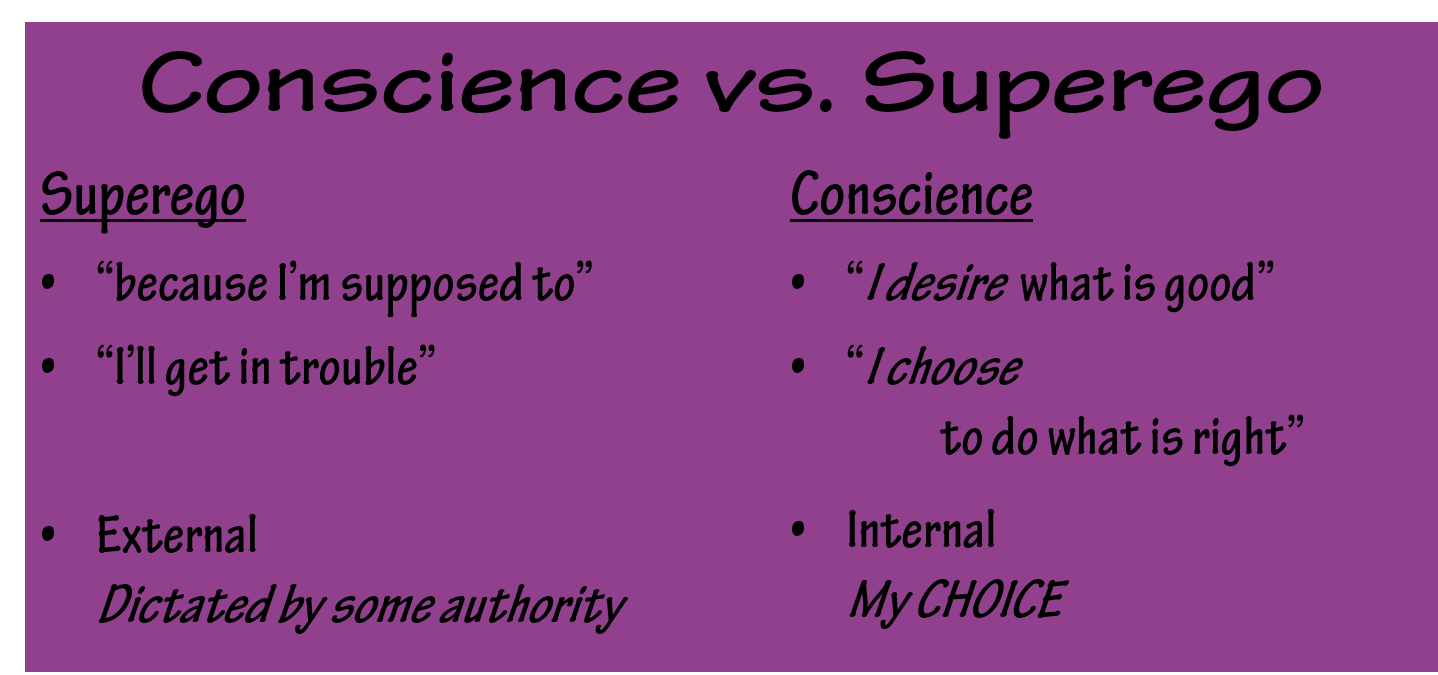

When discussing morality, lots of attention is given to the importance of following one’s conscience. In

Morality Part 2, I explained the difference between conscience and superego.

Superego has its place in forming our conscience, but they are not the same thing. From childhood to adulthood, we must transition from an external voice of moral authority to listening to the inner voice of our conscience. The Greek philosopher Plato explored this idea in both The Republic and Meno. Recognizing that one’s conscience reflects genuine internal decision, he asked:

Can you teach someone to be virtuous?

You can teach someone

what is right, but for them to be truly virtuous, they must actually choose it for themselves. So how do we actually

teach virtue? We teach virtue in three different ways, during three different stages of life.